The History of South Bristol

South Bristol has evolved and changed over more than five centuries. Before the arrival of Europeans in the late 15th century, the Pemaquid Peninsula, the shore of Johns Bay, the islands, and the Damariscotta River were used extensively by Native Americans, as is evident by numerous shell middens and prehistoric archeological sites. The mouth of the Pemaquid River was the site of a major Native American settlement, and the South Bristol “Gut” was part of the important inside passage for Native American travels. Another passage, evidenced by shell middens, was the short portage between Seal Cove on the Damariscotta River and Poorhouse Cove on Johns Bay. Explorers arrived on the midcoast during the early 1500s. One such exploration is that of Giovanni da Verrazzano, who recorded trading with Indians in 1528 at Small Point, a few miles west of South Bristol, and then sailing among the islands and sheltered harbors northeast of there on his way back to France. [1] By that time fishing trips from Europe to the northeast coast of North America were regular occurrences.

During the early 1600s, Englishman John Smith explored and mapped much of the coast of what is now Maine. [2] Legend has it that he spent Christmas of 1614 anchored in the well protected harbor of Christmas Cove on Rutherford Island, thus giving the cove its name. However, Capt. Smith could not have been here for Christmas, since his 1614 voyage lasted only from April until October of that year, when he arrived back in England. [3] The same schedule is described by Rowe [4] who also states that the voyages were intended to encourage colonization.

Europeans came regularly to the area in the late 16th and early 17th centuries to fish and explore the coast. These early settlers were farmers, fishermen, and traders. The “Gut” and east side of the Damariscotta River, which would become South Bristol, had scattered residents by the late 17th century. Pemaquid, with its fort, was a frontier marking the border between the English and French dominions. Friction between the English, French, and Native Americans caused a series of wars that devastated the area and resulted in the abandonment of the peninsula in the 1680s.

Resettlement of the peninsula did not occur until the 1730s when Scotch-Irish families were brought to the mid-coast region by Colonel David Dunbar under an English Royal mandate. Walpole, on the Damariscotta River; Harrington, at the head of Johns Bay; and Pemaquid Village were the first settled areas. In this second wave the settlers were farmers and woodsmen. They created homesteads from the forested land and exported timber, stone, bricks, and hay. Several Walpole families became wealthy as traders and large land owners. After weathering further Indian wars in the mid-1700s, the area grew and prospered with many of the forefathers of well-known South Bristol families arriving in the latter part of the 18th century.

In 1765, Bristol became one of the earliest incorporated towns in the Province of Maine, then part of Massachusetts. The growing comunities needed gathering places for religious services and town meetings. In 1772, Meeting Houses were built in Walpole, Harrington, and Round Pond. The Walpole and Harrington meetinghouses survive today, used for special events and open to the public. Bristol was involved in the Revolutionary War with soldiers defending the local coast and participating in battles around Boston.

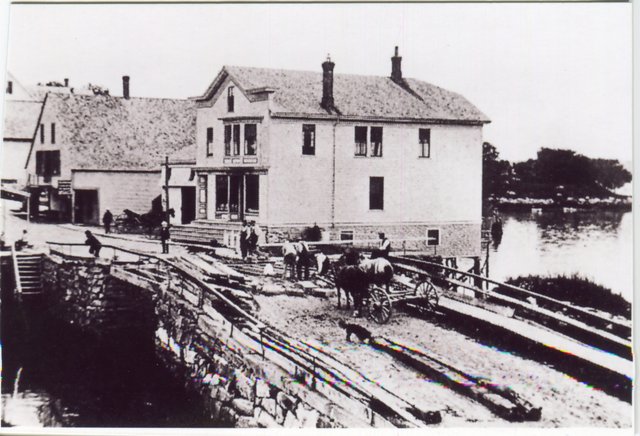

By the start of the 19th century, Walpole was the economic and population center of the east side of the Damariscotta River. At the same time, serious problems with land ownership surfaced. Claiming property ownership under 17th century Indian deeds and Royal land grants, heirs of earlier proprietors sought to force the current “squatters” either to pay dearly for, or to vacate, their hard-won and valuable farms. To quell rising violence, the Massachusetts authorities settled land claims in favor of the “squatters.”

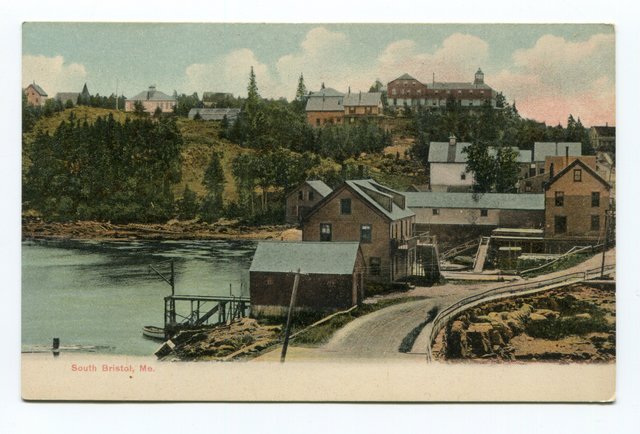

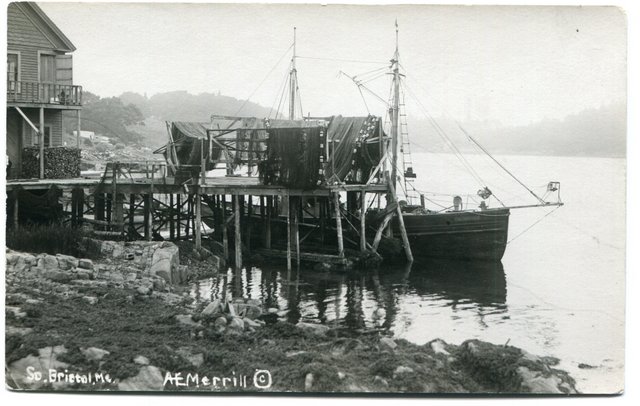

The economic disaster of the War of 1812 damaged the trading economy of the Damariscotta River communities and resulted in much hardship in Walpole. By the time of Maine’s statehood in 1820 as half of the Missouri Compromise, fishing, both near- and off-shore, was starting to become an important economic force on the Bristol peninsula. The rise of South Bristol village and Rutherford Island as a population center dates from that time. With the waning of timber and farming exports, fishing and boat building became the prominent occupations of South Bristol residents. While subsistence farming was still practiced in Walpole, fishermen made up a large percentage of the population at Clarks Cove, South Bristol, and Rutherford Island. South Bristol had several small fishing fleets and dried fish exporters. The Town also provided many seamen for the larger fishing fleets of Boothbay and Southport and had family ties to the Gloucester fishing industry. Ship and boat building had become an important business in the community by the 1850s.

The Bristol peninsula sent its quota of men to the Civil War. Men from South Bristol were represented in several well-known regiments, including the 20th Maine of Gettysburg fame. The Union Navy had many South Bristol seamen. The post Civil War depression was off-set on the Bristol peninsula by the boom of the menhaden, or pogy, fishery. These oily fish were abundant during the 1870s, and the mid-coast of Maine was the center of the fishery. South Bristol had three factories converting menhaden to valuable oil and fish meal. Many of the finer houses in South Bristol village date from this time of prosperity.

With the collapse of the pogy fishery by 1880, the area suffered difficult economic times. The slow exodus of families to the west increased in the 1880s, and the Bristol area population fell. Farming, fishing, and boat building continued, and commercial ice harvesting and exporting took place at Clarks Cove. However, with improved transportation, including steamships, small river steamboats, and trains, summer tourists were becoming more important to the mid-coast. In 1897, the Union Church was built, but it was not until 1903 that it became organized as a congregation with its first minister, Reverend C. Wellington Rogers. [5]

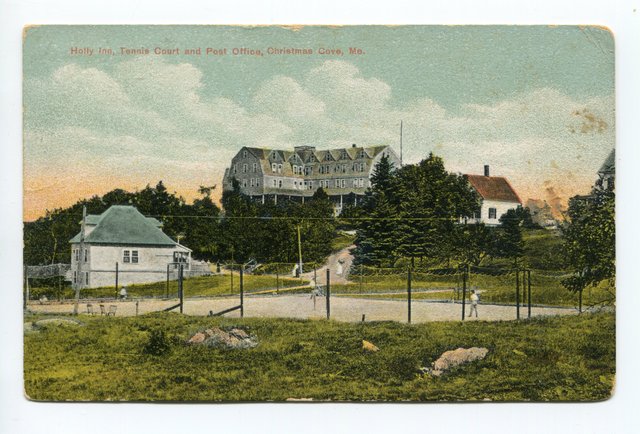

Starting with a summer colony on Inner Heron Island in the 1890s, Christmas Cove, South Bristol, and Clarks Cove were welcoming summer visitors to hotels, boarding houses, and tea rooms by 1900. The construction of shore cottages soon led to a full-fledged summer colony centered on Christmas Cove. The Christmas Cove Improvement Association was founded in 1900 [6] and many shore estates date from this period. By the early 20th century, Christmas Cove had become a yachting destination. Providing services to summer visitors became, and has remained, a major element of the local economy.

Transportation continued to improve in the early decades of the 20th century with steamboat service to Damariscotta and the arrival of the automobile in 1911. By 1913, however, South Bristol residents were growing dissatisfied with local governance under the Town of Bristol. Among their complaints was the Town’s failure to maintain the bridge, roads, and sidewalks in South Bristol; the unequal treatment of South Bristol’s schools in comparison to those in Bristol; and the distance to the Bristol High School, which made it virtually unavailable to the tax payers of South Bristol. The result was a series of petitions from South Bristol residents to the state legislature seeking separation from the Town of Bristol. Finally in 1915, South Bristol became a separate town comprised of Walpole, Clarks Cove, South Bristol village, and Rutherford and Inner Heron islands.

Through World War I, the Great Depression, and World War II, the Town had numerous family farms, several boat builders, and a small fishing industry, along with the all-important “summer trade.” The Harvey Gamage Shipyard, started in 1926, provided employment for many skilled boat builders, as did boatyards in East Boothbay. During World War II the Gamage yard built wooden minesweepers for the United States Navy. After the war, the Gamage yard put South Bristol on the map with construction of many large wooden fishing and sailing vessels. It was said that at one time half of the New Bedford, Massachusetts fishing fleet had been built in South Bristol.

The 1960s and 1970s saw the beginning of significant changes. Lobstering became the dominant fishery. Better roads allowed easier access to the Town, resulting in an increase in summer residences. Farming in the northern part of South Bristol declined, and more year-round residents were traveling out of town to work at places like Bath Iron Works. The Gamage Shipyard as a builder of wooden, and briefly steel, vessels came to an end in 1981. The Town became increasingly dependent on the stores and services of Damariscotta. Retirees made up a larger percentage of the Town’s population, reflecting a regional trend.

While South Bristol’s population grew overall, the number of children in the school system declined from 1950s levels. Shore front property, especially on Rutherford Island, became valuable and scarce. The Ira C. Darling Marine Center of the University of Maine opened in 1965 and has become an internationally recognized marine biology research center.

Today there are several remaining sites that give a glimpse into the early history of the Town. The Thompson Ice House is now a museum open to the public. Ice is still harvested from the adjacent pond every winter and stored in the ice house for summer use. Exhibits show the ice harvesting process and the tools used. The Walpole Meeting House is still used periodically for religious services, meetings, weddings, and musical performances. The site of the original Gamage Shipyard is now a marina with boat storage and a repair facility. Of the five schools that served the Town in the 19th century, the S Road School (c.1860 to 1943) remains. This one-room schoolhouse, called the Roosevelt School at the time it closed, has been restored to its appearance in the 1930s by the South Bristol Historical Society. It is open to the public. Private sites of historic significance include the Sproul Homestead and the Emily Means House, both on the National Register of Historic Sites along with the Walpole and Harrington meetinghouses and the Thompson Icehouse.

For more on the history of South Bristol, see Nelson W. Gamage, A Short History of South Bristol, Maine [7], presently out of print but available at the Rutherford Library and the South Bristol Historical Society; Ellen Vincent, Down on the Island, Up on the Main [8]; and H. Landon Warner, A History of the Families and Their Houses. [9] The South Bristol Historical Society located on Rutherford Island has extensive holdings open to the public and is on line at www.southbristolhistoricalsociety.org/.

References:

[1] Morrison, Samuel Eliot; The European Discovery of North America: The northern voyages; New York; Oxford University Press; 1971; pp. 308-9.

[2] Fischer, David Hackett; Champlain’s Dream; New York; Simon & Schuster; 2008; p. 228.

[3] Burrage, Henry Sweetzer, D.D.; The Beginnings of Colonial Maine: 1602-1658; Portland, Maine; Marks Printing House; 1914; p. 131.

[4] Rowe, William Hutchison; The Maritime History of Maine; New York; W. W. Norton & Company; 1948; p. 21.

[5] Sewall, Jane; The Marks that We Follow: A study of churches and religions of Mid-coast Maine; unpublished; 1978; available at South Bristol Historical Society.

[6] Wells, Stan and Ellen; The Christmas Cove Improvement Association 1900 – 2000: A Centennial History; South Bristol, Maine; Christmas Cove Improvement Association; 2000; p. 1.

[7] Gamage, Nelson w.; A Short History of South Bristol Maine; unpublished; no date; available at the Rutherford Library and the South Bristol Historical Society.

[8] Vincent, Ellen; Down on the Island, Up on the Main; South Bristol, Maine; South Bristol Historical Society; 2003.

[9] Warner, H. Landon; A History of the Families and Their Houses; South Bristol Maine; South Bristol, Maine; South Bristol Historical Society; 2006.